permaculture design principles

The essence of Permaculture:

Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability

by David Holmgren, publisher Holmgren Services 2002

permaculture in a nutshell

permaculture is an approach to land management and settlement design that adopts arrangements observed in flourishing natural ecosystems. it includes a set of design principles derived using whole-systems thinking. it applies these principles in fields such as regenerative agriculture, town planning, rewilding, and community resilience. the term was coined in 1978 by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, who formulated the concept in opposition to modern industrialized methods, instead adopting a more traditional or "natural" approach to agriculture

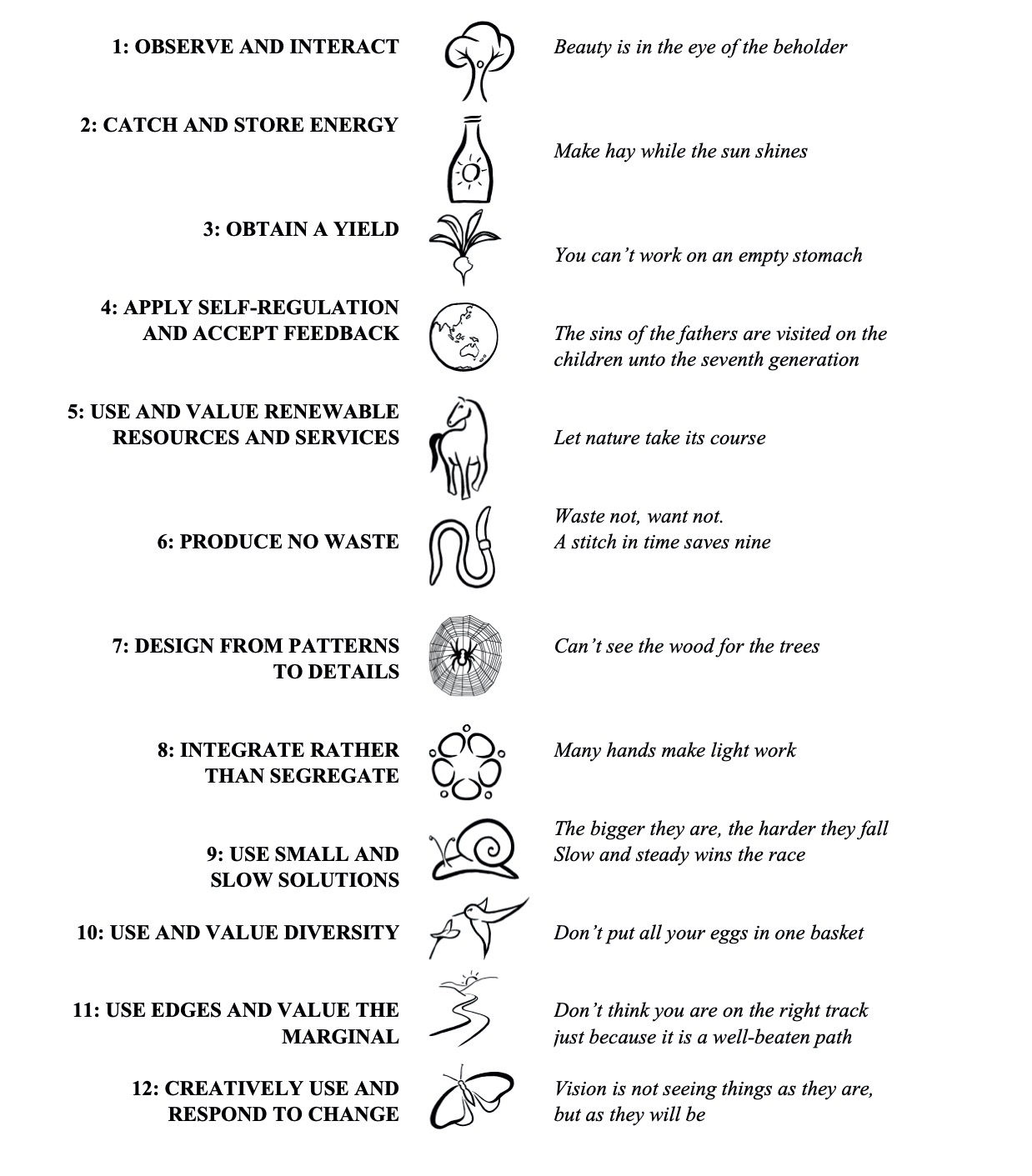

principles of permaculture

ethics are the moral principles that are used to guide action toward good and right outcomes and away from bad and wrong outcomes.

ethics act as constraints on survival instincts and the other personal and social constructs of self- interest that drive human behaviour in any society.

they are culturally evolved mechanisms formore enlightened self-interest, a more inclusive view of who and what constitutes “us” and a longer-term understanding of good and bad outcomes.

the greater the power of human civilisation (due to energy availability) and the greater the concentration and scale of power within society, the more critical ethics become in ensuring long-term cultural—and even biological—survival. this ecologically functional view of ethics makes them central in the development of a culture for energy descent.

like design principles, ethical principles were not explicitly listed in early permaculture literature. since the development of the Permaculture Design Course, ethics have generally been covered by three broad maxims or principles:

earth care

people care

fair share

(set limits to consumption and reproduction, and redistribute surplus)

these principles were distilled from research into community ethics, as adopted by older religious and cooperative groups. The third principle, and even the second, can be seen as derived from the first.

Essence of Permaculture Page 5/16

The Essence of Permaculture (2nd Ed) Extracts from Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability by David Holmgren 2002

OBSERVE AND INTERACT

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

Good design depends on a free and harmonious relationship to nature and people, in which careful observation and thoughtful interaction provide the design inspiration, repertoire and patterns. It is not something that is generated in isolation, but through continuous and reciprocal interaction with the subject.

Permaculture uses these conditions to consciously design our energy descent pathway.

In hunter-gatherer and low-density agricultural societies, the natural environment provided all material needs, with human effort mainly required for harvesting. In pre-industrial societies wit high population densities, agricultural productivity depended on large and continuous input of human labour. Industrial society depends on large and continuous inputs of fossil fuel energy to provide its food and other goods and services. Permaculture designers use careful observation and thoughtful interaction to reduce the need for both repetitive manual labour and for non-renewable energy and high technology.

In a world where the quantity of secondary (mediated) observation and interpretation threatens to drown us, the imperative to renew and expand our observation skills (in all forms) is at least as important as the need to sift and make sense of the flood of mediated information. Improved skills of observation and thoughtful interaction are also more likely sources of creative solutions than brave conquests in new fields of specialised knowledge by the armies of science and technology.

The icon for this principle is a person as a tree, emphasising ourselves in nature and transformed by it. It can also be envisaged as the keyhole in nature through which one sees the solution.

The proverb “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” reminds us that the process of observing influences reality and that we must always be circumspect about absolute truths and values.

CATCH AND STORE ENERGY

Make hay while the sun shines.

We live in a world of unprecedented wealth, resulting from the harvesting of the enormous storages of fossil fuels created by the earth over billions of years. We have used some of this wealth to increase our harvest of the earth’s renewable resources to an unsustainable degree. Most of the adverse impacts of this over-harvesting will show up, as available fossil fuels decline. In financial language, we have been living by consuming global capital in a reckless manner that would send any business bankrupt.

We need to learn how to save and reinvest most of the wealth that we are currently consuming or wasting, so that our children and descendants might have a reasonable life. The ethical foundation for this principle could hardly be clearer. Unfortunately, conventional notions of value, capital, investment and wealth are not useful in this task.

Inappropriate concepts of wealth have led us to ignore opportunities to capture local flows of both renewable and non-renewable forms of energy. Identifying and acting on these opportunities can provide the energy by which we can rebuild capital, as well as provide us with an “income” for our immediate needs.

This principle deals with the capture and long-term storage of energy, that is, savings and investment to build natural and human capital. The generation of income (for immediate needs) is dealt with in Principle 3: Obtain a yield.

The icon of sunshine captured in a bottle suggests the preserving of seasonal surplus and a myriad of other traditional and novel ways to catch and store energy. It also reflects the basic lesson of biological science: that all life is directly or indirectly dependent on the solar energy captured by green plants.

The proverb “make hay while the sun shines” reminds us that we have limited to time to catch and store energy before seasonal or episodic abundance dissipates.

OBTAIN A YIELD

You can’t work on an empty stomach.

The previous principle focused our attention on the need to use existing wealth to make long-term investments in natural capital. But there is no point in attempting to plant a forest for the grandchildren if we haven’t got enough to eat today.

This principle reminds us that we should design any system to provide for self-reliance at all levels (including ourselves) by using captured and stored energy effectively to maintain the system and capture more energy. More broadly, flexibility and creativity in finding new ways to obtain a yield will be critical in the transition from growth to descent.

Without immediate and truly useful yields, whatever we design and develop will tend to wither while elements that do generate immediate yield will proliferate. Whether we attribute it to nature, market forces or human greed, systems that most effectively obtain a yield, and use it most effectively to meet the needs of survival, tend to prevail over alternatives.

A yield, profit or income functions as a reward that encourages, maintains and/or replicates the system that generated the yield. In this way, successful systems spread. In systems language these rewards are called positive feedback loops that amplify the original process or signal. If we are serious about sustainable design solutions, then we must be aiming for rewards that encourage success, growth and replication of those solutions.

The original permaculture vision promoted by Bill Mollison of growing gardens of food and useful plants rather than useless ornamentals is still an important example of the application of this principle. The icon of the vegetable with a bite taken shows the production of something that gives us an immediate yield but also reminds us of the other creatures who are attempting to obtain a yield from our efforts.

APPLY SELF-REGULATION AND ACCEPT FEEDBACK

The sins of the fathers are visited on the children unto the seventh generation

This principle deals with self-regulatory aspects of permaculture design that limit or discourage inappropriate growth or behaviour. With better understanding of how positive and negative feedbacks work in nature, we can design systems that are more self-regulating, thus reducing the work involved in repeated and harsh corrective management.

Self-maintaining and regulating systems might be said to be the Holy Grail of permaculture: an ideal that we strive for but might never fully achieve.

Traditional societies recognised that the effects of external negative feedback are often slow to emerge. People needed explanations and warnings, such as “the sins of the fathers are visited on the children unto the seventh generation” and “laws of karma” which operate in a world of reincarnated souls.

In modern society, we take for granted an enormous degree of dependence on large-scale, often remote, systems for provision of our needs, while expecting a huge degree of freedom in what we do without external control. In a sense, our whole society is like a teenager who wants to have it all, have it now, without consequences.

Much of the ecologically dysfunctional aspects of our systems result from this denial of the need for self-regulation and feedback systems that control inappropriate behaviour by simply delivering the consequences of that behaviour back to us. John Lennon’s song “Instant Karma” suggests that we will reap what we sow much faster than we think. The speed of change and increasing connectivity of globalisation may be the realisation of this vision.

The Gaia hypothesis of the earth as a self-regulating system, analogous to a living organism, makes the whole earth a suitable image to represent this principle. Scientific evidence of the earth’s remarkable homeostasis over hundreds of millions of years highlights the earth as the archetypical self-regulating whole system, which stimulated the evolution, and nurtures the continuity, of its

USE AND VALUE RENEWABLE RESOURCES

AND SERVICES

Let nature take its course

Renewable resources are those that are renewed and replaced by natural processes over reasonable periods, without the need for major non-renewable inputs. In the language of business, renewable resources should be seen as our sources of income, while non-renewable resources can be thought of as capital assets. Spending our capital assets for day-to-day living is unsustainable in anyone’s language. Permaculture design should aim to make best use of renewable natural resources to manage and maintain yields, even if some use of non-renewable resources is needed in establishing the system.

In restoring the balance between renewable and non-renewable resource use, it is often forgotten that these “new ideas” were the norm not so long ago. The joke about the environmentally aware person using a solar clothes dryer (washing line) is funny because it works on the very recent nature of much of this takeover of functions by technology and fossil fuels.

Renewable services (or passive functions) are those we gain from plants, animals and living soil and water without them being consumed. For example, when we use a tree for wood we are using a renewable resource, but when we use a tree for shade and shelter, we gain benefits from the living tree which are non-consuming and require no harvesting energy. This simple understanding is obvious and yet powerful in redesigning systems where many simple functions have become dependent on non-renewable and unsustainable resource use.

Permaculture design should make best use of non-consuming natural services to minimise our consumptive demands on resources and emphasise the harmonious possibilities of interaction between humans and nature. There is no more important example in history of human prosperity derived from non-consuming use of nature’s services than our domestication and use of the horse for transport, soil cultivation and general power for a myriad of uses. Intimate relationships to domestic animals such as the horse also provide an empathetic context for the extension of human ethical concerns to include nature.

The proverb “Let nature take its course” reminds us that human intervention and complication of processes can make things worse and that we should respect and value the wisdom in biological systems and processes.

PRODUCE NO WASTE

Waste not, want notA stitch in time saves nine

This principle brings together traditional values of frugality and care for material goods, the mainstream concern about pollution, and the more radical perspective that sees wastes as resources and opportunities.

The industrial processes that support modern life can be characterised by an input–output model, in which the inputs are natural materials and energy while the outputs are useful things and services. However, when we step back from this process and take a long-term view, we can see all these useful things end up as waste. This model might be better characterised as “consume–excrete”. The view of people as simply consumers and excreters might be biological, but it is not ecological.

Bill Mollison defines a pollutant as “an output of any system component that is not being used productively by any other component of the system”. This definition encourages us to look for ways to minimise pollution and waste through designing systems to make use of all outputs. In response to a question about plagues of snails in gardens dominated by perennials, Mollison was in the habit of replying that there was not an excess of snails but a deficiency of ducks.

The earthworm is a suitable icon for this principle because it lives by consuming plant litter (wastes), which it converts into humus that improves the soil environment for itself, for soil micro- organisms and for the plants. Thus the earthworm, like all living things, is a part of web where the outputs of one are the inputs for another.

The proverb “waste not, want not” reminds us that it is easy to be wasteful when there is an abundance but that this waste can be the cause of later hardship. “A stitch in time saves nine” reminds us of the value of timely maintenance in preventing waste and work involved in major repair and restoration efforts.

DESIGN FROM PATTERNS TO DETAILS

Can’t see the wood for the trees

The first six principles tend to consider systems from the bottom-up perspective of elements, organisms, and individuals. The second six principles tend to emphasise the top-down perspective of the patterns and relationships that tend to emerge by system self-organisation and co-evolution. The commonality of patterns observable in nature and society allows us to not only make sense of what we see but to use a pattern from one context and scale to design in another. Pattern recognition, discussed in Principle 1: Observe and interact, is the necessary precursor to the process of design.

The spider on its web, with its concentric and radial design, evokes zone and sector site planning, the best-known and perhaps most widely applied aspect of permaculture design. The design pattern of the web is clear, but the details always vary.

Modernity has tended to scramble any systemic common sense or intuition that can order the jumble of design possibilities and options that confront us in all fields. This problem of focus on detail complexity leads to the design of white elephants that are large and impressive but do not work, or juggernauts that consume all our energy and resources while always threatening to run out of control. Complex systems that work tend to evolve from simple ones that work, so finding the appropriate pattern for that design is more important than understanding all the details of the elements in the system.

The proverb “Can’t see the wood (forest) for the trees” reminds us that the details tend to distract our awareness of the nature of the system; the closer we get the less we are able to comprehend the larger picture.

INTEGRATE RATHER THAN SEGREGATE

Many hands make light work.

In every aspect of nature, from the internal workings of organisms to whole ecosystems, we find the connections between things are as important as the things themselves. Thus “the purpose of a functional and self-regulating design is to place elements in such a way that each serves the needs and accepts the products of other elements.”16

Our cultural bias toward focus on the complexity of details tends to ignore the complexity of relationships. We tend to opt for segregation of elements as a default design strategy for reducing relationship complexity. These solutions arise partly from our reductionist scientific method that separates elements to study them in isolation. Any consideration of how they work as parts of an integrated system is based on their nature in isolation.

This principle focuses more closely on the different types of relationships that draw elements together in more closely integrated systems, and on improved methods of designing communities of plants, animals and people to gain benefits from these relationships.

The ability of the designer to create systems that are closely integrated depends on a broad view of the range of jigsaw-like lock-and-key relationships that characterise ecological and social communities. As well as deliberate design, we need to foresee, and allow for, effective ecological and social relationships that develop from self-organisation and growth.

The icon of this principle can be seen as a top-down view of a circle of people or elements forming an integrated system. The apparently empty hole represents the abstract whole system that both arises from the organisation of the elements and also gives them form and character.

In developing an awareness of the importance of relationships in the design of self-reliant systems, two statements in permaculture literature and teaching have been central:

each element performs many functions

each important function is supported by many element

The connections or relationships between elements of an integrated system can vary greatly. Some may be predatory or competitive; others are co-operative, or even symbiotic. All these types of relationships can be beneficial in building a strong integrated system or community, but permaculture strongly emphasises building mutually beneficial and symbiotic relationships. This is based on two beliefs:

we have a cultural disposition to see and believe in predatory and competitive relationships, and discount co-operative and symbiotic relationships, in nature and culture

Co-operative and symbiotic relationships will be more adaptive in a future of declining energy.

Permaculture can be seen as part of a long tradition of concepts that emphasise mutualistic and

shift the general perception of these concepts from romantic idealism to practical necessity.

symbiotic relationships over competitive and predatory ones.

USE SMALL AND SLOW SOLUTIONS

The bigger they are, the harder they fall. Slow and steady wins the race.

Systems should be designed to perform functions at the smallest scale that is practical and energy- efficient for that function.

Human scale and capacity should be the yardstick for a humane, democratic and sustainable society. Whenever we do anything of a self-reliant nature—growing food, fixing a broken appliance, maintaining our health—we are making very powerful and effective use of this principle. Whenever we purchase from small, local businesses or contribute to local community and environmental issues, we are also applying this principle.

The speed of movement of materials and people (and other living things) between systems should be minimised. A reduction in speed reduces total movement, increasing the energy available for the system’s self-reliance and autonomy.

Speed, especially of personal movement, generates high levels of stimulation that drown out the subtle and the quiet. For example, when we drive somewhere new, we are stimulated by what we see in the landscape. When we travel the same route regularly, we may notice small changes but generally we lose interest and become bored. However, if we ride a bicycle or walk over the same route, our eyes, ears, skin and noses are opened to a new world of subtle stimulation that the enclosure and speed of the car had kept from us.

The spiral house of the snail is small enough to be carried on its back and yet capable of incremental growth. With its lubricated foot, the snail easily and deliberately traverses any terrain. Although it is the bane of gardeners, the snail is an appropriate icon for small scale and slow speed.

The proverb “the bigger they are, the harder they fall” is a reminder of one of the disadvantages of size and excessive growth. The proverb “slow and steady wins the race” is one of many that encourages patience while reflecting a common truth in nature and society.

USE AND VALUE DIVERSITY

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

The spinebill and the humming bird both have long beaks and the capacity to hover, perfect for sipping nectar from long, narrow flowers. This remarkable co-evolutionary adaptation symbolises the specialisation of form and function in nature.

The great diversity of forms, functions and interactions in nature and humanity are the source for evolved systemic complexity. The role and value of diversity in nature, culture and permaculture is itself complex, dynamic, and at times apparently contradictory. Diversity needs to be seen as a result of the balance and tension in nature between variety and possibility on the one hand, and productivity and power on the other. It is now widely recognised that monoculture is a major cause of vulnerability to pests and diseases, and therefore of the widespread use of toxic chemicals and energy to control these. Polyculture is one of the most important and widely recognised applications of the use of diversity, but is by no means the only one.

Diversity in different cultivated systems reflects the unique nature of site, situation and cultural context. Diversity of structures, both living and built, is an important aspect of this principle, as is the diversity within species and populations, including human communities.

The proverb “don’t put all your eggs in one basket” embodies the common sense understanding that diversity provides insurance against the vagaries of nature and everyday life

USE EDGES AND VALUE THE MARGINAL

Don’t think you are on the right track just because it is a well-beaten path

The icon of the sun coming up over the horizon with a river in the foreground shows us a world composed of edges.

Tidal estuaries are a complex interface between land and sea that can be seen as a great ecological trade market between these two great domains of life. The shallow water allows penetration of sunlight for algae and plant growth, as well as providing forage areas for wading and other birds. The fresh water from catchment streams rides over the heavier saline water that pulses back and forth with the daily tides, redistributing nutrients and food for the teeming life.

Within every terrestrial ecosystem, the living soil, which may only be a few centimetres deep, is an edge or interface between non-living mineral earth and the atmosphere. For all terrestrial life, including humanity, this is the most important edge of all. Deep, well drained and aerated soil is like a sponge, a great interface that supports productive and healthy plant life. Only a limited number of hardy species can thrive in shallow, compacted and poorly drained soil, which has insufficient edge.

Eastern spiritual traditions and martial arts regard peripheral vision as a critical sense that connects us to the world quite differently to focused vision. This principle reminds us to maintain awareness, and make use, of edges and margins at all scales, in all systems. Whatever is the object of our attention, we need to remember that it is at the edge of any thing, system or medium that the most interesting events take place; design that sees edge as an opportunity rather than a problem is more likely to be successful and adaptable. In the process, we discard the negative connotations associated with the word “marginal” in order to see the value in elements that only peripherally contribute to a function or system.

The proverb “don’t think you are on the right track just because it is a well-beaten path” reminds us that the most common, obvious and popular is not necessarily the most significant or influential.

CREATIVELY USE AND RESPOND TO CHANGE

Vision is not seeing things as they are but as they will be

This principle has two threads: designing to make use of change in a deliberate and co-operative way, and creatively responding or adapting to large-scale system change which is beyond our control or influence. The acceleration of ecological succession within cultivated systems is the most common expression of this principle in permaculture literature and practice. These concepts have also been applied to understand how organisational and social change can be creatively encouraged. As well as using a broader range of ecological models to show how we might make use of succession, I now see this in the wider context of our use of, and response to, change.

In Permaculture One we stated that, although stability was an important aspect of permaculture, evolutionary change was essential. Permaculture is about the durability of natural living systems and human culture, but this durability paradoxically depends in large measure on flexibility and change. Many stories and traditions have the theme that within the greatest stability lie the seeds of change. Science has shown us that the apparently solid and permanent is, at the cellular and atomic level, a seething mass of energy and change, similar to the descriptions in various spiritual traditions.

The butterfly, which is the transformation of a caterpillar, is a suitable icon for the idea of adaptive change that is uplifting rather than threatening.

While it is important to integrate this understanding of impermanence and continuous change into our daily consciousness, the apparent illusion of stability, permanence and sustainability is resolved by recognising the scale-dependent nature of change discussed in Principle 7: Design from patterns to details. In any particular system, the small-scale, fast, short-lived changes of the elements actually contribute to higher-order system stability. We live and design in a historical context of turnover and change in systems at multiple larger scales, and this generates a new illusion of endless change with no possibility of stability or sustainability. A contextual and systemic sense of the dynamic balance between stability and change contributes to design that is evolutionary rather than random.

The proverb “vision is not seeing things as they are but as they will be” emphasises that understanding change is much more than the projection of statistical trend lines. It also makes a cyclical link between this last design principle about change and the first about observation.

instagram: @philipp.vonhase